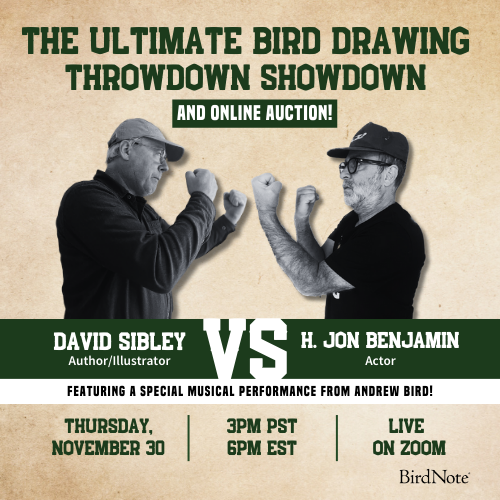

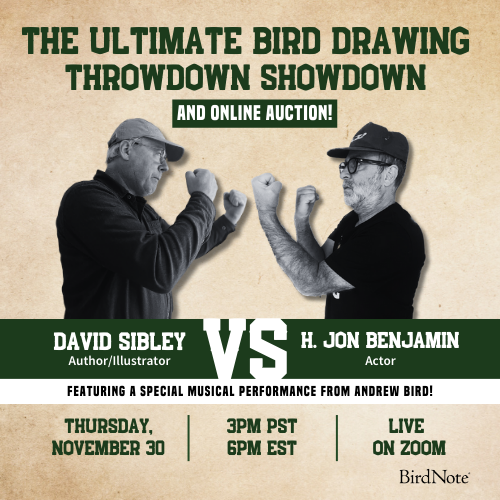

Join BirdNote tomorrow, November 30th!

Illustrator David Sibley and actor H. Jon Benjamin will face off in the bird illustration battle of the century during BirdNote's Year-end Celebration and Auction!

Beginning in 1911, miners in Great Britain carried a canary in a cage with them down into the mines. Why? Carbon monoxide can build to deadly levels, and it has no smell. If the canary weakened or stopped singing, miners knew to get out of the mine — and quickly. Why use a bird instead of, say, a mouse? It all had to do with the birds’ breathing anatomy: canaries get a dose of air when they inhale and when they exhale, thus a double dose of toxic gases. Thankfully, in 1986, more humane electronic warning devices replaced them.

BirdNote®

Canary in a Coal Mine

Written by Bob Sundstrom

This is BirdNote.

[“Going to the Mine” - Bob Fox and Benny Graham in How Are You Off for Coals]

For at least 75 years, miners in Great Britain carried a live canary in a cage every day as they went down into the mines.

[Island Canary, domestic form song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/79093, 0.07-.15]

So, how did this practice start? Miners began using canaries in 1911, based on the advice of Scottish scientist John Haldane. He reasoned that a singing bird would be a good indicator of carbon monoxide — the gas can build to deadly levels in mines, and it has no smell. When a canary began to weaken, or stopped singing, miners knew to get out of the mine — and quickly.

But why use a bird as an alarm instead of, say, a mouse? Haldane understood a bird’s breathing anatomy. And he knew that as birds breathe, they get a dose of air both as they inhale and as they exhale. Compared to mice — or to miners — canaries would get a double dose of toxic gases. Their reactions served as an early warning of danger.

The little birds with the big song served alongside British miners until 1986, when more humane electronic warning devices replaced them.

For BirdNote, I’m Mary McCann.

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 79093 recorded by Andrea L Priori.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org July/August 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# canary-01-2017-08-10 canary-01

[Island Canary, domestic form song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/79093, 0.07-.15]