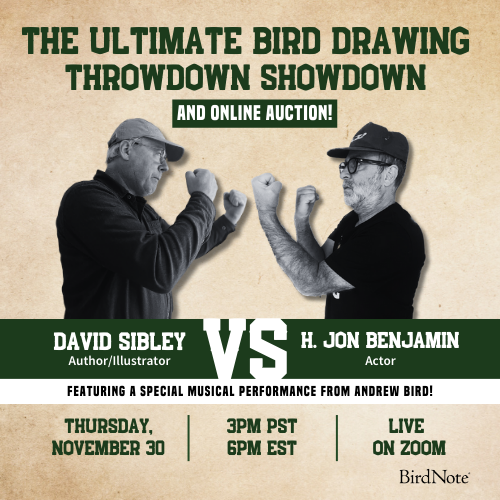

Join BirdNote tomorrow, November 30th!

Illustrator David Sibley and actor H. Jon Benjamin will face off in the bird illustration battle of the century during BirdNote's Year-end Celebration and Auction!

In Puerto Rico, there is an area of saline lagoons, salt flats and mangrove swamps where humans have extracted salt for over 500 years. We often describe the effects of human activity on the environment as negative. But the migratory birds that eat and rest in one of the most visited places by locals and tourists probably see things differently.

Listen to this episode in Spanish here.

Ari Daniel: BirdNote Presents.

[Echoing Wingflaps SFX]

[Threatened inspiration theme starts]

Ari Daniel: This is Threatened, and I’m your host Ari Daniel. When we talk about the effect of human activity on the environment in this show, it often has a negative impact. But this isn’t always the case. We’ve already heard some stories from Puerto Rico about the positive impacts that people can have on the birds in their communities. Mariana Reyes, where are you taking us today–our final episode of the season?

Mariana Reyes: Hi Ari. I can’t believe this is our last episode!

Ari Daniel: I know!

Mariana Reyes: Today, I'm excited to take you somewhere I have visited many times. The Salt Flats in Cabo Rojo, or Las Salinas de Cabo Rojo as we say in Spanish. It is one of my favorite places. It is beautiful and has a fascinating history. I discovered it is an important place for birds on the island and migratory birds you can see in North, Central, and South America.

Ari Daniel: Oh wow. It sounds amazing. Let’s go!

[Music starts: Las Batatas - Viento De Agua]

Mariana Reyes: The Salt Flats in Cabo Rojo is an area of saline lagoons, salt flats, and mangrove swamps where humans have extracted salt for over 500 years. The Taínos, the indigenous people of the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico, had a system established to remove salt before the Spaniards arrived in the 15th century. Thirty years ago, a group of residents from the municipality of Cabo Rojo organized to protect the natural area, which includes 1800 acres of coastal land. The process has been ongoing ever since...

[Wilderness ambience from Cabo Rojo]

Mariana Reyes: Cabo Rojo is two and a half hours away from the capital, San Juan. It is on the southwestern tip of the island. In the salt flats, there are mountains of salt that look like mountains of snow. All around, you can see lagoons of different sizes, filled with saline water of various shades of earthy pink. The lagoons extend almost as far as what my eyes can see… until it meets the bright blue of the Caribbean Sea.

[Wilderness ambience from Cabo Rojo]

The meeting of waters happens on the beach known as Playuela, or Playa Sucia. On a much wider scale, it is also where the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea come together. The clear and calm water borders a red cliff of over 200 feet, where there is a 19th-century lighthouse. Some people say the red cliff gives Cabo Rojo its name.

The salt flats are also where different groups convene to manage the natural area. You can find a local company extracting salt, government agencies facilitating scientific research, and community groups offering guided tours.

Ari Daniel: Mariana, this place you’re describing reminds me of the Nemours Wildlife Foundation in South Carolina. I got to go there last year with Dr. Drew Lanham for a Threatened episode we called Plantation Ecology. The place had been transformed by the forced labor of people who’d been enslaved for the production of rice, but like Cabo Rojo it’s become a haven for birds. And even though rice is no longer grown there, it’s maintained by people to support the wildlife that came to depend on it.

Mariana Reyes: Yes, it is a similar story in that the transformation of a natural area happens both for colonial and commercial reasons. In over 500 years, the salt flats went from being used by the Taínos to being managed by the Spanish government, later by American companies, and today by a local company. Of course, the history is long and complex.

To get us started on learning part of that history, I spoke with Oscar Diaz, a retired biologist who worked for the US Fish and Wildlife Services in Puerto Rico. Oscar has been a key figure in many conservation projects across the island. And he was in charge of establishing and managing the first one in the Salt Flats in Cabo Rojo, where he worked from 2007 to 2016.

Oscar Diaz: Cabo Rojo National Wildlife Refuge. It's only about 1800 acres, about 1,800 acres. But wait a second. It's not about size. It's about the importance in-the ecological importance of the areas that you manage. Well Cabo Rojo being so small is very, very important for the purposes of conserving migratory and resident shorebirds.

Mariana Reyes: These days, the salt flats are managed by a local company, Empresas Padilla. The salt extracted is sold mainly to pharmaceutical companies that produce a wide variety of medicines in Puerto Rico. According to Oscar, the general public must be involved in protecting the natural area.

Oscar Diaz: We need, we need, and the need have to be in capital letters. We need to incorporate our people, our citizens. Everybody in Puerto Rico have to be conscious of the important resources that we have in this little piece of island and the ones that we are basically destroying almost every day, almost every day.

Mariana Reyes: The salt flats represent an interesting case because what is at stake is not a specific animal species but an entire ecosystem that migratory birds now depend on. And what makes it possible to conserve the natural area is actually the commercial production of salt.

Oscar Diaz: In my short life, I have seen at least three species of coquis that are gone forever, forever. They don't exist anymore on planet earth.

Mariana Reyes: The coquí is a tiny frog that fits on a fingertip and is endemic to Puerto Rico. It usually sings at night and is a national symbol on the island.

Oscar Diaz: The Puerto Rican Parrot, you know, there were only 13 parrots in the whole planet in 1973. We have more than 800 parrots in Puerto Rico today

[Inspirational music starts]

Thanks to an effort, you know, Puerto Ricans, North Americans, a lot of conservationists, a lot of biologists, a lot of scientists, but more than that, a lot of Puerto Ricans who really, really get the Puerto Rican Parrots in their heart. And it's now part of their lives and nobody's gonna touch a Puerto Rican Parrot.

Humans has been manipulating these coastal areas to allow the salt water, the sea salt, the sea water coming into very, very shallow areas. And then they close at one moment the entrance of the sea water. And then the water start evaporating and eventually, you know, the salt, uh, gets concentrated on the ground in the continual evaporation of water. The salt precipitates, and then they start extracting the salt.

Mariana Reyes: This process creates the conditions in which a lot of animals can thrive, including the brine shrimp that is an important food source for migrant birds.

[Puerto Rican Wilderness soundscape fades up]

Biologist Alcides Morales works for the organization Para la Naturaleza dedicated to the preservation of the land. They manage an area at Punta Guaniquilla near the salt flats.

Alcides Morales: Las Salinas de Cabo Rojo, aunque es un espacio natural que es un espacio que ha estado ahí por milenios, depende de ese manejo y esa conexión con el ser humano que ha estado llevándose a cabo por más de 500 años, sino miles de años.

Mariana Reyes: Alcides points out that the Salt Flats in Cabo Rojo is a natural area that has existed for millennia thanks to human activity. To the management and connection with humans for over 500 years.

Alcides Morales: Pero esas prácticas de manejo son las que benefician irónicamente, a mantener estos niveles de agua apropiados. Así que está entrelazado, el buen manejo para la extracción de sal y proveer y mantener el hábitat para estas aves playeras.

[Wilderness fades out]

Mariana Reyes: He goes on to say that, ironically, the natural area depends on the very management practices that create the mountains of salt and the pink lagoons. In other words, human activity is needed at the salt flats in Cabo Rojo to keep water at the appropriate levels to produce salt and provide food and shelter for migratory birds.

[Driving upright bass starts: Lowball - Blue Dot Session]

Ari Daniel: At Cabo Rojo we humans have created, over centuries, an ecosystem that birds depend on. It’s unique in the Caribbean and important for birds undertaking incredible migrations. When we get back from the break, we go there to learn more about the birds and the people working to protect and maintain the salt flats.

[Music fades]

[MIDROLL]

[Music starts: Threatened Motion theme]

Ari Daniel: Welcome back. We’re heading out to the Cabo Rojo Salt Flats with producer Mariana Reyes.

[Cabo Rojo soundscape fades up]

[Sound of walking on dirt]

Mariana Reyes: I traveled to Cabo Rojo to speak with some of the people that work to maintain the land, and educate the public about this amazing place. Here, dry forest meets the Caribbean and every sunset seems like a gift from nature. It is a place where many of us come to to get away from San Juan, especially during the Summers.

The committee of caborrojenos was created in 1990 by a group of citizens concerned about the fact that the area needed to be managed and cared for in the long run. They first went to the local agency of natural resources but they were told that there was no budget to manage the area, so they finally talked to the federal Fish and Wildlife Service and created a partnership. One of their goals was to preserve the area and keep it available for the public to enjoy.

The group is called El Comité Caborrojenos pro Salud y Ambiente, or in English The Committee of Caborrojenos for Health and the Environment. The community organization joined forces with the federal government to preserve the area. Pedro Valle, a professor retired from the University of Puerto Rico, is the president.

Pedro Valle: El grupo de caborrojeños entra en conversaciones con el servicio federal de pesca y vida silvestre con el propósito de establecer un tipo de centro de visitantes, de forma tal de que esta parte estuviera abierta al público. Como está ahora, porque si no lo hubieran cercado y le hubieran puesto letreros de No trespassing.

Mariana Reyes: There are different things at stake here. On the one hand, the preservation of the natural resources that depends on the commercial use of the land, and there is also the determination of the locals to be able to have access to the land and keep the trails and bird observation stations available to the general public.

One of the aspects managed by the committee is the tour operation and I’m here to join one of the volunteers that will tell me more about the space where a lot of people come for birdwatching because there are close to 200 bird species, including 28 species of migratory shorebirds.

[Faint calls of migratory shorebirds]

Dafne Javier is a volunteer guide at the salt flats and a retired professor of Business Administration from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez. She is also part of the Caborrojeños Committee and is enthusiastic about their work. I joined one of her tours and walked through the area.

Dafne Javier (on tour): Bienvenidos. Welcome. You are in a dry forest. Uh, we are going to see everything in the dry forest. There are lots of birds today. And watch out for the thorns [laughs]. There will be thorns in this forest.

Dafne Javier: The Interpretive Center of Salina of Cabo Rojo is the principal stopover for the seashore birds. They come here from Canada, they stop here to eat. They eat like two or three weeks. A special brine shrimp that we have here. We have two lagoons that are very, very shallow and they come and they eat at their leisure. This is a protected forest and they know it. So nobody will bother them. So they're very quiet and they eat very good. And then they fly to Argentina. Uh, it varies when they come and it varies at quantity. They don't come at the same time all over. But you can see them. And it's fantastic seeing the different species eating in the Lagoons.

[Shorebirds calling]

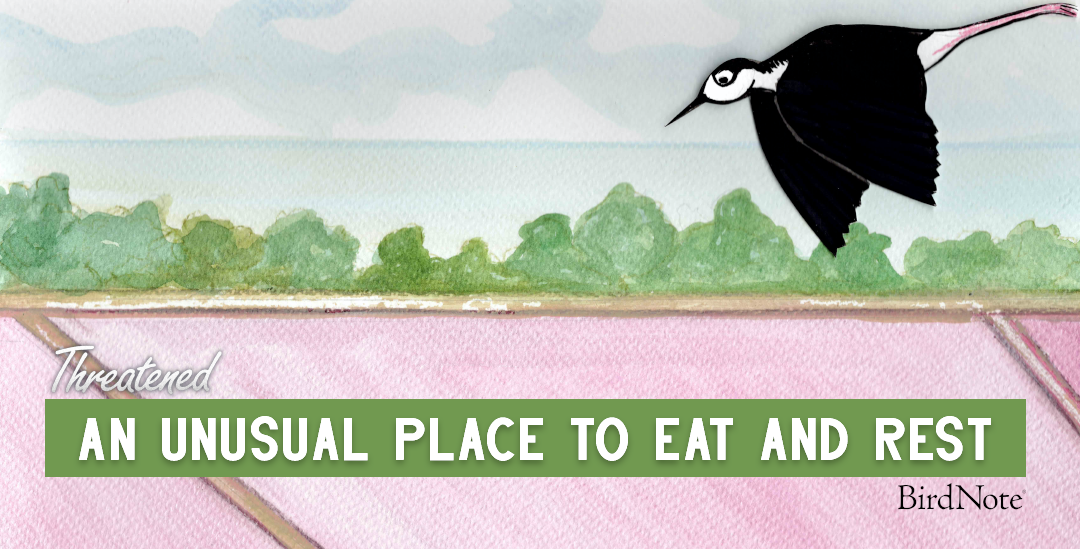

Mariana Reyes: We learned that migratory birds stop at the salt flats for food and shelter.

Dafne Javier: This is not a rainforest. This is a dry forest.

Mariana Reyes: You can find groups of Black-necked Stilt birds splashing their long pink legs in the lagoons. The Black-necked Stilt has black wings and a white belly, which makes it look like it is wearing a black dress, which is why we call it viuda in Spanish!

Dafne Javier on Tour: El pajaro se ponen el arbol, y que hacen el arbol, despues de comer?

Child on Tour: Despues de comer, es de romper la semilla.

Dafne Javier on Tour: Y despues?

Child on Tour: Y a …

Dafne Javier on Tour: Exactamente!

Mariana Reyes: Other birds that depend on the salt flats are Snowy Plovers,

[Snowy Plover calls]

Wilson's Plovers,

[Wilson’s plover calls]

and Willets.

[Willet calls]

The lagoons have shallow water levels that support lots of aquatic insects and brine shrimp that shorebirds can eat to recharge and continue their journey. The algae and some bacteria are also what gives the water its pink color. The number of species reported on eBird for Cabo Rojo is 177, which is higher than any other location on eBird on the southwest coast of Puerto Rico.

[Cabo Rojos soundscape]

Adrianne Tossas is the president of Birds Caribbean, an organization that works to preserve birds in the region, and we are meeting with her here in Cabo Rojo to talk about the relevance of this area for local and migratory birds.

Adrianne Tossas: Welcome to this part of the island where is one of the places where we have more diversity in birds. Birds Caribbean members and partners. We all work for the conservation of bird species under habitats, and we are all facing the same threats. Mainly, it’s habitat loss because of the growth of the human population, the urban sprawl. This is the major problem because we destroy the habitats and when our species don't have the places to breed like forest, but also the coastal habitats where, where most cities are built, this is a big issue for seabirds and also for shorebirds.

[Cabo Rojos soundscape fades]

Mariana Reyes: So now that the human made ecosystem of the salt flats is necessary for the birds if it disappears there is no where else for the birds to go.

[Upright bass music starts: Flatlands - Blue Dot Sessions]

Birds Caribbean is doing even more research in the area and leading an effort to track these birds more closely.

Adrianne Tossas: We recognized the importance of this place and Birds Caribbean this year, installed monitoring tracking station. It’s part of a collaboration we have with partners on the northeastern coast of North America. This is part of a MOTUS collaboration and with this station, we can track shorebirds or other migratory birds that have special tags. And we can learn about the migration route. Since this year we have this station at the salt flats in Cabo Rojo. Birds Caribbean is planning to install these stations in different islands, along all the migration route of shorebirds.

Mariana Reyes: Motus is the tracking system, developed by Birds Canada, that follows birds movement with a tracking device. But there was no tracking in the Caribbean, until now. The Birds Caribbean project led by Adrienne is about to change that.

Ari Daniel: That’s so cool Mariana! You know, I learned about this Motus technology last year, too, in a bonus episode we did in Pennsylvania. These tracking tags they’ve developed are so small they can be used on creatures as tiny as a dragonfly. It’s wonderful that the tech’s expanding, and I can’t wait to hear what they’ll learn from this project in Puerto Rico.

Mariana Reyes: Absolutely, the more evidence and data we have to back up our knowledge that this is a special and important place, the better we can protect it.

Ari Daniel: Mariana, you said that this is a place you’ve visited many times. After learning about its importance for the birds, I’m curious, does it change the way you look at it or feel when you’re there?

[Adventurous guitar music starts]

Mariana Reyes: Well, to me, all this new information makes it an even more magical place. The Salt Flats in Cabo Rojo is a curious example of an ecosystem made by humans that, over time, became vital for animals and plant species. The management of the natural area by the commercial, government, and community groups is evidence of what joint efforts can do for land conservation. The only way to protect the salt flats is by extracting salt and keeping the shallow waters that migratory birds like so much. The strategy seems to be working.

[Guitar music fades]

[Festive music starts: Fiesta De Plena - Vient De Agua]

During this series we have discovered that there are many efforts in Puerto Rico that have successfully led to the preservation of birds and their habitats. Local communities together with scientists and government agencies have been able to protect the Puerto Rican Parrot, the habitat of the Julian Chivi and to call attention to the general public about the San Pedrito.

[Festive music fades]

[Threatened Theme starts]

Ari Daniel: This season has really highlighted for me that we know how to protect birds. We just have to work together. It’s not always easy for people to do that, but when we consider all the perspectives and we place actual value on birds, we can save these habitats and species that are at risk. Mariana, thanks so much for reporting these stories with us.

Mariana Reyes: Thank you, Ari. It’s been a pleasure. You can always come visit and watch some birds.

Ari Daniel: Oh I would love that.

This episode was produced by Mariana Reyes Anglero, Joanne Gil Rivera and me, Ari Daniel. It was edited by Laura Marina Boria. It was sound designed and mixed by Leah Shaw Dameron. Fact-checking by Conor Gearin. Our theme song and original music were composed by Ian Coss, with additional music by Viento de Agua. Threatened is a production of BirdNote and overseen by Content Director Allison Wilson. You can find a transcript of this show and additional resources, BirdNote’s other podcasts, and much more at BirdNote.org. Thanks for listening.